By popular demand, I show here a long history of 2-yr and 10-yr swap spreads. The reader may judge for himself how good these spreads are at capturing systemic risk and anticipating recessions. And, of course, to what degree spreads today are pointing to a double-dip recession.

Friday, September 30, 2011

Money supply update

I have commented several times on the unprecedented rise in M2 growth that started in late June. (See posts here, here, and here) I have been arguing that the increase in M2 was being driven by a capital flight from Europe; concerned that Eurozone banks were at risk of failure should there be a significant sovereign default, depositors were frantically shifting their funds into U.S. banks. This still looks to be the case, but the latest developments reflect a significant—and positive—change for the better.

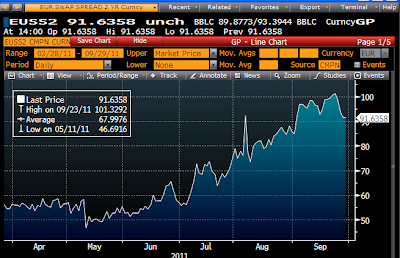

As the first chart shows, M2 is no longer growing rapidly, as of the last few weeks. The bulge amount to almost $400 billion of "extra" M2, above and beyond the 5-6% growth pace of M2 that has prevailed since 1995. My first clue as to what was driving the increase of M2 was the huge rise in 2-yr Eurozone swap spreads, and swap spreads again appear to be explaining the behavior of M2. As the next chart shows, swap spreads have stopped rising, and M2 growth has leveled off.

This next chart compares the level of 2-yr Eurozone swap spreads (orange line) with the level of M2 (white line). Both started rising about the same time, and both seem to have peaked at about the same time. 2-yr Eurozone swap spreads are an excellent proxy for the systemic risk and the fears of bank failures that have engulfed the Eurozone financial system. If swap spreads are no longer rising, then it would make sense for the capital flight out of Europe to be slowing down.

I can't prove that Eurozone swap spreads and capital flight out of Europe are what have boosted M2, but the correlation shown in the above chart is too much of a coincidence to ignore. The message here is that we may have seen the worst of the Eurozone sovereign debt and banking crisis. If so, that should prove to be a tremendous relief for equity markets everywhere.

Swap spread update

Swap spreads continue to be excellent, market-based, forward-looking indicators of financial and economic troubles ahead. The swap market is highly liquid, and spreads are a very good indicator not only of counterparty risk (typically large banks) but also of systemic risk. When swap spreads rise above their "normal" range of 25-35 bps, then that means there are some real problems brewing in the economy.

Today, U.S. 2-yr swap spreads are only 33 bps, and they have been within a normal range throughout the current business cycle expansion. They are telling us that financial markets are healthy and enjoy sufficient liquidity, and this is consistent with an economy that is growing, however slowly. There are no hidden surprises out there just waiting to ambush us. Spreads have picked up a little this year, but that can be traced to worries about the health of European financial markets, where 2-yr swap spreads are almost 100 bps. Europe has a problem—the very real threat of sovereign debt defaults—but we don't have anything like that.

Another market-based indicator of risk is the yield on junk bonds; the higher the yield, the weaker the economy and the higher the risk that leveraged borrowers might default. Junk bond yields now average 8.4%, according to Bloomberg, 30 bps lower than their average since the current recovery began, and only 20 bps higher than their average since the beginning of last year. Junk yields are 210 bps lower today than they were at the onset of the 2008-09 recession.

Taken together, these two indicators are not even close to signaling a double-dip recession.

And did I mention that corporate profits are at all-time nominal, real, and GDP-relative highs? Businesses have fired lots of people and become lean and mean and profitable. Where is the impetus for another round of huge cutbacks of the size necessary to ambush overall growth?

Still no sign of a double-dip

Today's data releases weren't particularly newsworthy—more of a mixed bag. Personal income in August was a bit weaker than expected, while personal spending was about as weak as expected; the personal consumption deflator was a tiny bit higher than expected; the Chicago and Milwaukee ISM indices for September were stronger than expected; and the Univ. of Michigan confidence number was higher than expected. Since the income and spending data is old news, and we know the economy has been weak for the past several months, the ISM data from this month might actually be some genuine good news, but we need to wait for the overall ISM number on Monday to be sure. And as I noted yesterday, the very up-to-date claims number shows no economic deterioration at all.

The chart above uses the August data for inflation, and yesterday's data for interest rates, so it is a fairly accurate picture of the current state of monetary policy. The real Fed funds rate is a good proxy for how "easy" or "tight" the Fed is: the higher the rate the tighter. Currently the Fed's policy rate is as easy as it been since the inflationary 1970s, when the Fed consistently failed to raise its target rate fast enough to get ahead of rising inflation. The slope of the Treasury curve from 1 to 10 years is also a good indicator of how easy or tight the Fed is; a steeper slope in the yield curve suggests easy money, while a flat or negative (inverted) slope suggests very tight money. So a relatively high red line and a relatively low blue line are strong confirmations that monetary policy today is easy.

As the chart illustrates, recessions have always been preceded by a significant tightening of monetary policy: a flat to negatively-sloped yield curve, and a relatively high real Fed funds rate. The early years of a recovery are typically just the opposite, which is what we have today. For all its efforts to artificially depress the long-term bond yields, the yield curve still has a relatively steep, positive slope. And of course real borrowing costs are clearly negative. Using the headline PCE deflator gives you a real Fed funds rate of -2.5%, which would be close to a record low on this chart.

So monetary policy is still quite "easy" and thus the likelihood of a recession is very low. Yet I see more and more analysts predicting that we are on the cusp of another recession, most notably the folks at ECRI. I could always be wrong, but another recession at this juncture would fly in the face of a lot of historical evidence to the contrary.

Thursday, September 29, 2011

Thoughts on GDP and inflation

Today's revisions to Q2/11 GDP growth were relatively small and thus not very significant, but I thought this chart was interesting. Note how nominal GDP growth has been running right around 4% for the past seven quarters. It's the composition of nominal GDP growth that has changed; real growth has declined, while inflation has risen (inflation being the difference between the blue and red bars). Put another way, the rise in inflation has corresponded to a decline in growth.

This chart plots the quarterly annualized rate of inflation according to the GDP deflator, the broadest measure of inflation available, and it makes the recent rise in inflation really stand out. We left deflation behind once the recovery started in the summer of 2009. All measures of inflation have risen meaningfully since then. Inflation is not yet at scary levels, to be sure, but it is a fact of current life. We're not really in "stagflation" mode yet (inflation is still too low to be a big concern), but if nominal GDP rises from here without a meaningful pickup in real growth, then it would be the 1970s deja vu.

Note also how inflation by this measure rose from a low of 1.1% in late 1998 (when real growth reached 5.0%), to a high of 4.7% in March '07 (when real growth dipped to a low of 1.2%). This runs directly counter to what the Fed's Phillips-Curve inspired theories of inflation predict: strong growth does not lead to rising inflation—rather, low inflation leads to strong growth, and weak growth lends itself to rising inflation.

This is just one more way of saying that the Fed's efforts to stimulate the economy with easy money and artificially low interest rates are more likely to stimulate inflation than they are to stimulate real growth.

Claims continue to slowly decline

Next month unadjusted claims should, if seasonal patterns repeat themselves, begin to climb through year-end. If they don't, then we will see some pretty substantial declines in the adjusted numbers. Stay tuned, this could be interesting.

Wednesday, September 28, 2011

A tale of two PIIGS (cont.)

A little over a month ago, I highlighted the extreme divergence between Greece and Ireland, both of which have been on the short list of major sovereign debtors that are likely to default. Both Greece and Ireland faced crushing debt and deficit burdens, but Ireland's prospects had improved dramatically relative to Greece's (since it's 2-yr government yields were far lower), thanks to Ireland's credible efforts to cut government spending.

In the past month, the yields on 2-yr Irish government debt have dropped almost 130 bps, while comparable Greek yields have soared 2600 bps. (Top chart shows Greek yields, while the bottom chart shows Irish yields.) Perhaps more interestingly, Irish 2-yr yields have dropped 180 bps in just the last week, and are now back to levels not seen since late February, while Greek yields remain stratospheric. This is change you can believe in; these market-based indicators are telling us that Greece is now almost certain to default, while Ireland stands a good chance of surviving intact. The likelihood of an Irish default is now significantly lower than it was just two months ago, because Ireland is on the road to salvation thanks to credible austerity measures.

Only two PIIGS now stand out as serious candidates for default: Greece ($475 billion of debt), and Portugal ($200 billion). Spanish yields ($800 billion of outstanding debt) are now down to a mere 3.33%, only 275 bps above comparable German debt—thanks in part to efforts to restructure and shore up its banking system. That's a spread that's only barely troubling. Italian yields are 100 bps above Spanish yields, so there's still some angst there, but it is amplified by the huge size of Italian government debt ($2.1 trillion), and the Italians' less-than urgent response to addressing their budget difficulties.

Some light is appearing at the end of the sovereign debt tunnel, and it is reflected in the recent drop in 2-yr Euro swap spreads. Even if Greece and Portugal go bust, it's not too difficult to believe that the Eurozone banking system and economy can survive as long as the other PIIGS continue to work towards credible solutions.

UPDATE: John Cochrane has a coherent argument in the WSJ ("Last Chance to Save the Euro") for why the best solution would be to just let Greece default. Greece is incapable of credibly advancing an austerity agenda, and trying to paper over the problem with ECB debt purchases only delays the inevitable. Allowing Greece to default would preserve the ECB's balance sheet and its credibility. And it might even teach Greece a valuable lesson.

UPDATE: The WSJ has good article which puts meat on the bones of just how effective Ireland's austerity measures have been.

The people are VERY upset, and that is good

In case you haven't seen it, I post this chart from Gallup. The country as a whole has never been so dissatisfied with the way the country is being governed. This chart gets my vote for the most important of the year.

Key findings:

• 82% of Americans disapprove of the way Congress is handling its job.

• 69% say they have little or no confidence in the legislative branch of government, an all-time high and up from 63% in 2010.

• 57% have little or no confidence in the federal government to solve domestic problems, exceeding the previous high of 53% recorded in 2010 and well exceeding the 43% who have little or no confidence in the government to solve international problems.

• 53% have little or no confidence in the men and women who seek or hold elected office.

• Americans believe, on average, that the federal government wastes 51 cents of every tax dollar, similar to a year ago, but up significantly from 46 cents a decade ago and from an average 43 cents three decades ago.

• 49% of Americans believe the federal government has become so large and powerful that it poses an immediate threat to the rights and freedoms of ordinary citizens. In 2003, less than a third (30%) believed this.

All of this has major implications for next year's elections, since the election will essentially be a referendum on fiscal policy. Do you believe taxes should rise to pay for current and projected levels of spending, or do you believe that spending should be brought into line with the existing tax rate structure? Do you believe that more government spending and regulation of the economy will improve the outlook, or do you believe that less spending and regulation will?

Judging by the findings above, I have to believe that the elections will be the catalyst for a significant change in fiscal policy, in the direction of spending restraint and at the very least an avoidance of higher tax rates. This shift in the mood of the electorate has been underway for some time now, beginning with the emergence of the Tea Party, and it found its greatest expression in last November's elections. As a supply-sider, I have welcomed this shift from the very beginning, since I strongly believe it will prove to be very positive for the long-term financial and economic outlook.

In short, things are so bad right now that they are almost surely going to get better.

Business investment still strong

August new orders for capital goods came in much stronger than expected (+1.1% vs. +0.4%), and July orders were upwardly revised by 0.7%, so the combination of the two has put this series back on a double-digit growth track. Four months ago, I noted that this series had really slowed down, but now the outlook appears much brighter. Back then, the annualized growth rate of capex over the previous six months was only 5%. After numerous revisions, the number is now 13.7%. Over the six months ending in August, capex is up at a very strong 18.4% annualized rate, and orders are now just 1% shy of their all-time high. What a difference a few revisions can make!

This news has to qualify as a major blow to the prevailing view that the economy is approaching "stall speed" and therefore at risk of slipping into another recession. Businesses are still facing terrible headwinds (e.g., the highest corporate tax rate in the industrialized world, mountains of new regulatory burdens, difficulties in getting loans), but they are nevertheless forging ahead with an optimism that is impressive. There is every reason to believe that the economy is still growing, albeit at a somewhat disappointing pace.

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

China is not a currency manipulator

Harry Reid thinks he's more likely to pass a bill labeling China a "currency manipulator" than he is to pass the jobs bill that Obama repeatedly urges Congress to pass "right now." He's probably right, but not because China is a currency manipulator.

The claim—popular among politicians and industries forced to compete with Chinese imports—that China is manipulating its currency by keeping it too weak is tough to square with the facts. As the top chart shows, the Chinese yuan has been steadily appreciating against the dollar since 1994, for a cumulative gain of 36%. The second chart shows the real, inflation-adjusted value of the yuan vis a vis a large basket of currencies, and here again we see the yuan has appreciated significantly: since early 1994 the yuan has appreciated by a whopping 58%.

Reid is not going to waste his time with Obama's jobs bill, because he knows it is no good and thus is going nowhere. He would do well to back off the China-bashing also, since it would be a very bad move. The only purpose of the "currency manipulator" finding would be to impose tariffs on Chinese imports, and those would presumably benefit only a small minority of industries and their workers, while punishing everyone else with higher prices and more inflation.

Yes, China has been "manipulating" its currency, but only in the direction of making it stronger, in part to avoid letting the yuan follow the dollar down against other currencies. This makes it more difficult for its industries to compete in the U.S., but it also raises China's standard of living—by making imports cheaper—and keeps inflation at bay. There's nothing wrong with that, and we could benefit from a stronger dollar as well.

UPDATE: I forgot to mention one other very important fact: by continually revaluing upwards the yuan vis a vis the dollar, the Chinese are unilaterally reducing the value to them of their considerable holdings of Treasury securities—some $1.2 trillion. In just the past year, raising the yuan/dollar exchange has cost the Chinese approximately $70 billion. And we want them to do this even more?

UPDATE: Dan Ikenson at Cato has a good article which goes into detail about why branding China a currency manipulator would be a big mistake.

The claim—popular among politicians and industries forced to compete with Chinese imports—that China is manipulating its currency by keeping it too weak is tough to square with the facts. As the top chart shows, the Chinese yuan has been steadily appreciating against the dollar since 1994, for a cumulative gain of 36%. The second chart shows the real, inflation-adjusted value of the yuan vis a vis a large basket of currencies, and here again we see the yuan has appreciated significantly: since early 1994 the yuan has appreciated by a whopping 58%.

Reid is not going to waste his time with Obama's jobs bill, because he knows it is no good and thus is going nowhere. He would do well to back off the China-bashing also, since it would be a very bad move. The only purpose of the "currency manipulator" finding would be to impose tariffs on Chinese imports, and those would presumably benefit only a small minority of industries and their workers, while punishing everyone else with higher prices and more inflation.

Yes, China has been "manipulating" its currency, but only in the direction of making it stronger, in part to avoid letting the yuan follow the dollar down against other currencies. This makes it more difficult for its industries to compete in the U.S., but it also raises China's standard of living—by making imports cheaper—and keeps inflation at bay. There's nothing wrong with that, and we could benefit from a stronger dollar as well.

UPDATE: I forgot to mention one other very important fact: by continually revaluing upwards the yuan vis a vis the dollar, the Chinese are unilaterally reducing the value to them of their considerable holdings of Treasury securities—some $1.2 trillion. In just the past year, raising the yuan/dollar exchange has cost the Chinese approximately $70 billion. And we want them to do this even more?

UPDATE: Dan Ikenson at Cato has a good article which goes into detail about why branding China a currency manipulator would be a big mistake.

Bond market roller-coaster

It's a rare event to see 30-yr T-bond yields moving up by 37 bps in the space of the three trading sessions, especially after they plunged almost 50 bps in the previous three trading sessions (see above chart). The change in yield equates to a 9% price rise, followed by a 6.2% price decline. This sort of volatility is a good measure of the market's deep-seated fear that a Greek default will set off another global tsunami of bank failures and a sickening global economic free-fall such as we saw in 2008. After all, 30-yr bond yields only move dramatically when the long-term outlook changes dramatically.

To put this into better context, the plunge in 30-yr yields during the past two months has been just about as dramatic as the unprecedented plunge in bond yields that occurred at the end of 2008, when markets were braced for a global financial market collapse that would translate into a multi-year global depression. Markets were just a tad too pessimistic back then, and I think we will see that today's pessimism is overdone as well. The bond market yield roller coaster ride is not over yet, and could prove pretty exciting for T-bond bears in the months to come if Greece manages anything short of an ugly default.

Job market update

The ASA Staffing Index, a measure of temporary and contract employment, rose 2.2% in the week ending Sept. 18th. It normally rises as the year progresses, especially as companies expand part-time staff to handle the holidays. This year has been no exception, but the rise in the index has been more muted than it was last year, and the index is 1.2% below where it was during the same week last year. This jibes with the slower pace of economic growth we've seen so far this year, but more importantly, it does not reflect any deterioration of the kind that would validate the FOMC's recently-expressed concern that "there are significant downside risks to the economic outlook."

Housing price update

Housing prices in major metropolitan markets on average are down almost 30% from their highs. But for the past 28 months, housing prices have been relatively stable, despite many predictions that they would suffer another collapse as defaults and foreclosures ramped up.

In real terms, prices in 10 major metropolitan markets are down about 38% from their highs.

Fixed-rate mortgage rates have declined from a little over 6% in 2006 to just over 4% today, and that translates into a 22% reduction in a homeowner's monthly mortgage rate for a given amount of borrowing. Added together, the decline in real housing prices and the decline in mortgage payments have reduced the effective cost of buying a house by about 50% in the past five years. That's a huge price adjustment, and it has served to clear the market. It's tough to imagine that housing will get much cheaper than it is today.

Monday, September 26, 2011

Money supply update

In partial rebuttal to my post yesterday, which asserted that the combination of huge deficits and a significant shortening of the maturity profile of Treasury debt posed the biggest proximate risk of rising inflation, monetary policy is still a critical issue, since at the end of the day inflation only happens if central banks allow it. In the article I referenced, Cochrane was not trying to argue that monetary policy has been inflationary; rather, he was arguing that it is quite possible that the Fed would be unable to respond adequately to a massive decline in money demand that could, in turn, be amplified by the very short-term nature of Federal borrowing needs. He recognizes that the Fed has provided all the kindling (i.e., a huge increase in bank reserves) that would be necessary for an inflationary conflagration, and what he focused on in his article was the origin of the spark that might set off a rising inflation fire.

So what follows is simply an update of where the monetary policy fundamentals stand today. The dry fuel for rising inflation is still there, but as yet it poses no immediate threat beyond the gradual increase in inflation we have seen in the past year, which I think is likely to continue.

Bank reserves are the raw material for the money supply, since banks must hold reserves against their deposits. Our fractional reserve monetary system allows banks to create new deposits (new money) if they can back up those deposits with some reserves. Beginning in Sept. '08, the Fed launched its first quantitative easing program, which ended up injecting about $1 trillion of bank reserves, more than 10 times the reserves that the Fed had created in its entire history. All things being equal (which they are most certainly not), this massive reserve expansion theoretically could have resulted in an equally massive increase in money, which almost surely would have led to a serious bout of higher inflation. Not content with simply scaring the bejeesus out of Fed watchers everywhere—myself included—the Fed embarked on a second quantitative easing program in October of last year, boosting the amount of reserves by another $600 billion. All of this reserve expansion was fueled by the purchase of $1.6 trillion of Treasury and Agency debt. Among other things, this means that the Fed essentially financed the federal government's deficit last year, a classic case of "debt monetization," the mere thought of which would have sent the world into a panic gold-buying binge. Oh, wait, isn't that what has already happened these past several years?

Most of the reserves that were created by open market purchases are still sitting idle, however, in the form of Excess Reserves held at the Fed. Banks are apparently content with holding onto these reserves, since they pay 0.25%, which is more than twice the yield that reserves earn in the overnight market (currently 0.1%), rather than using them to make new loans which take the form of increased deposits. To put it another way, the Fed has undertaken a massive reserve expansion in order to accommodate the banking system's intense desire for risk-free, short-term securities. As the chart above shows, Required Reserves have approximately doubled since the first quantitative easing program, from $45 billion to $93 billion, and $10 billion of this increase has come in just the past month. So only a tiny fraction of the $1.6 trillion reserve expansion has been used by banks to increase the money supply. That tiny fraction has grown significantly, however, and it reflects a rather significant—albeit of lesser magnitude—increase in the money supply.

Most of the impetus to the expansion of the M2 money supply comes not from the Fed or the banks, however. Money has increased as a result of the world's increased demand for money; to date, the Fed's actions have been primarily designed to ensure that increased demands for money could be accommodated by the banking system—that there would be no risk of any shortage of risk-free liquidity. The chart above makes it clear that the recent, unprecedented growth in the money supply is similar to what we have seen during financial market panics of the past. The amount of money in the economy has surged, not because the Fed has run the printing presses overtime, but because the world has desperately demanded more dollar cash as a hedge to the risk of European sovereign debt defaults. Accommodating a sharp rise in money demand is not in itself inflationary.

From a long-term perspective, the latest increase in M2 is not all that unusual, nor is it frightening from a monetarist's inflation perspective. M2 is only about $400 billion, or 4% above its long-term trend, which has been 6% annualized growth over the past 15 years, during which time inflation has averaged about 2.5% per year. It's the equivalent of a minor blip on the monetary radar screen. We've seen such blips in the past, and they have not resulted in dire or inflationary consequences.

Nevertheless, there are still reasons to be concerned about the risk of higher inflation. Unlike other times when money supply growth has surged, today the dollar is scraping the bottom of its valuation barrel. The dollar was much stronger in 2001 and at the height of the 2008 panic than it is today. A strong dollar is prima facie evidence of a relative shortage of dollars, so today's historically weak dollar suggests at the very least that whatever the Fed has done has resulted in a relative over-supply of dollars, and that is an essential ingredient for inflation.

During previous episodes of strongly rising money growth, commodities were either extremely weak (2001) or suffered massive price declines (2008). This also suggests that there is a relative abundance of dollars in the world today, and that commodities, even after falling over 10% since last April, still represent inflationary pressures that can eventually find their way into the prices of other goods and services.

Finally, although the chart above (5-yr, 5-yr forward inflation expectations) shows that the market's inflation expectations have fallen about 80 bps in the past two months, a similar decline occurred last summer, after which inflation by all measures ended up accelerating. Inflation expectations today are still much higher than they were at the end of 2008, and that also suggests that monetary policy is relatively accommodative.

The thrust of Cochrane's argument was that the greatly shortened maturity profile, and massive size, of outstanding Treasury debt could provoke a significant decline in money demand if the world began to doubt the U.S. government's ability to tame its almost-out-of-control spending. Trillions of dollars could potentially try to shift out of short-term Treasuries and into other goods and assets, and this would have the effect of greatly increasing the price level.

As this last chart (which uses a conservative estimate of only 2.5% annualized GDP growth in the current quarter) shows, money demand has skyrocketed since the onset of the 2008 recession. If money demand were to revert to the level that prevailed prior to 2008, the added M2 velocity (velocity being the inverse of money demand) could add 20% to nominal GDP growth (most of which would likely be in the form of higher inflation) in coming years.

Would the Fed be able to withdraw all the reserves it has added in time to prevent such a surge of inflation from occurring if money demand starts declining? That is the question which everyone is asking, and which is keeping people awake at night.

Sunday, September 25, 2011

Sunday reading

John Cochrane has written an excellent, though very long, article ("Inflation and Debt") on why the risk of inflation we face comes not from the Fed's monetary policy, but from our projected federal deficits. (HT: Greg Mankiw)

For several years, a heated debate has raged among economists and policymakers about whether we face a serious risk of inflation. That debate has focused largely on the Federal Reserve — especially on whether the Fed has been too aggressive in increasing the money supply, whether it has kept interest rates too low, and whether it can be relied on to reverse course if signs of inflation emerge.

But these questions miss a grave danger. As a result of the federal government's enormous debt and deficits, substantial inflation could break out in America in the next few years. If people become convinced that our government will end up printing money to cover intractable deficits, they will see inflation in the future and so will try to get rid of dollars today — driving up the prices of goods, services, and eventually wages across the entire economy. This would amount to a "run" on the dollar. As with a bank run, we would not be able to tell ahead of time when such an event would occur. But our economy will be primed for it as long as our fiscal trajectory is unsustainable.

Needless to say, such a run would unleash financial chaos and renewed recession. It would yield stagflation, not the inflation-fueled boomlet that some economists hope for. And there would be essentially nothing the Federal Reserve could do to stop it.

Cochrane's central point—one that I have missed—is that it is the dramatic shortening of the average maturity of Treasury debt that creates so much risk of inflation today:

... our government is now funded mostly by rolling over relatively short-term debt, not by selling long-term bonds that will come due in some future time of projected budget surpluses. Half of all currently outstanding debt will mature in less than two and a half years, and a third will mature in under a year. Roughly speaking, the federal government each year must take on $6.5 trillion in new borrowing to pay off $5 trillion of maturing debt and $1.5 trillion or so in current deficits.

As the government pays off maturing debt, the holders of that debt receive a lot of money. Normally, that money would be used to buy new debt. But if investors start to fear inflation, which will erode the returns from government bonds, they won't buy the new debt. Instead, they will try to buy stocks, real estate, commodities, or other assets that are less sensitive to inflation. But there are only so many real assets around, and someone has to hold the stock of money and government debt. So the prices of real assets will rise. Then, with "paper" wealth high and prospective returns on these investments declining, people will start spending more on goods and services. But there are only so many of those around, too, so the overall price level must rise. Thus, when short-term debt must be rolled over, fears of future inflation give us inflation today — and potentially quite a lot of inflation.

We have no choice but to put our fiscal affairs in order, and as soon as possible. Fortunately, the problem is still relatively easy to solve. Cochrane's solution is familiar to all serious students of what ails our economy today. What we need is 1) real entitlement reform, since "our largest long-term spending problem is uncontrolled entitlements," 2) more revenues, which can be achieved by a pro-growth lowering of tax rates, and 3) a reduction in regulatory burdens.

Cochrane's article is extensive, but written in a manner that should be accessible to just about anyone. He does a good job of explaining, from a monetarist's perspective, the mechanics of how inflation happens. Read the whole thing.

Friday, September 23, 2011

Corporate bond valuation update

This chart shows spreads on 5-yr credit default swaps, for investment grade and high yield corporate bonds. Spreads have surged since July, and are now back to levels that preceded and foreshadowed the onset of the worst of the Great Recession. Is this a sure sign that we are on the cusp of another recession? As much as I think spreads are excellent and forward-looking indicators of economic and financial market fundamentals, I don't think this chart shows the whole story.

This second chart compares 2-yr swap spreads to junk bond yields. Swap spreads are excellent and forward-looking indicators of systemic risk; today they are in the upper range of the levels (15-35 bps) that typically prevail when the economy is navigating relatively stable seas. Swaps did an excellent job of predicting the collapse of the junk bond market in 2008, and an excellent job of leading the huge rally that began in late 2008 and continued through last year. Today, swap spreads are signaling only mild upper pressure on junk yields—nothing to get very excited about.

So why are spreads on corporate debt (top chart) so high? It's mainly because the yields on Treasury debt are extraordinarily, incredibly low. The European sovereign debt crisis has created gigantic demand for Treasury debt, greatly depressing yields in the process. The big widening of corporate debt spreads is only partly due to a deterioration in the prospects for U.S. companies, and mostly due to the desperation that is gripping European investors.

Equity valuation update

This week's market swoon improved equity market valuations that were already attractive. The 12-mo. trailing PE of the S&P 500, according to Bloomberg, is now around 12.5, well below its 50-yr average of 16.6. On an earnings basis, equities are now yielding around 8%, much higher than the 5% yield on BAA corporate bonds, according to Moody's.

The only logical explanation for why valuations are so attractive is that the market fully expects a significant deterioration in corporate earnings in the years to come. Again, my point is that the market is priced to some very pessimistic assumptions. If things don't turn out to be as bad as the market now expects, then there is plenty of upside left in the stock market.

Thursday, September 22, 2011

What was missing in tonight's Republican debate

The Republican candidates for president are doing a good job of honing their anti-Obama and pro-growth, pro-jobs arguments. The election is shaping up to be epic because the choices couldn't be more stark or fundamental, and the outcome will undoubtedly have a profound impact on the future of the U.S. economy.

Obama has defined the liberal position in no uncertain terms: There is no way we can make any significant cuts in current and projected spending; to close the deficit we will need more taxes, and only the rich can afford to play that role. Meanwhile, we can grow the economy by giving the government more opportunities to direct the course of the economy.

The Republicans are making the exact opposite point: There is no way we can allow the government to remain as big as it is (close to a post-war high relative to GDP), and there is no way we can impose higher tax rates on this economy; to close the deficit we will need to reduce the size and role of government. We can grow the economy by relying less on government to make decisions for us, and more on individuals and free markets to make the right choices.

If you believe that government can administer the economy's scarce resources better than the private sector, vote Democrat. If you believe the private sector administers those scarce resources better than government bureaucrats, vote Republican.

So far, so good, but the Republicans are making three huge mistakes.

The biggest mistake the Republicans are making is on the subject of immigration. The party is veering far too much in the direction of isolationism, and the party is much too anti-immigrant for my taste.

This country was built by immigrants. I believe the vast majority of immigrants are people who are willing to risk everything in the hopes of creating a better life for themselves and their family in a place they've never been. Immigrants bring new blood into the country, new ambition, and yes, they compete with legal residents for jobs. But prosperity is not a zero-sum game. We can have more immigration and more jobs for everyone, if we have the right fiscal and monetary policies and if government gets out of the way of the private sector.

Why do we have so many illegal immigrants? So far, the only answer I've heard is that the federal government has failed to secure our borders. We have failed to keep out the people who desperately want to get in, to find work, and to improve their lives. So, according to most of the candidates, we need to build a bigger fence and devote more resources to policing the border.

I haven't heard anyone say that maybe we unwittingly have created huge, perverse incentives for immigrants to come, because we have a huge social safety net that is not too hard for anyone (including legal residents) to game. Build it and they will come; offer generous handouts and subsidies, and don't be surprised if all sorts of legal and illegal people sign up for a piece of the action.

I haven't heard anyone say that maybe we have so many illegal immigrants because we are making it extremely difficult for those who want to come here, to come legally. We have an immigrant quota system of roughly 500,000 per year, but many more than that want to come. I personally know several people who have waited 5 to 10 years to get a resident visa, because the countries they came from had huge waiting lists. Would you be willing to wait 10 years to take your family to America if you were suffering and willing to work hard?

One solution to our immigration problem would be to drastically increase our annual quotas, especially for those who are offered a job here by an existing business. As it is, work visas are extremely limited in number, and are often allotted in a matter of days, leaving businesses who want to hire a foreigner (perhaps one educated at our excellent universities) in the lurch for the rest of the year.

Another solution to the immigration problem would be to reduce the size of our social safety net. Fewer handouts and fewer subsidies would reduce the incentive to come for those who just want to take advantage of our generosity. Why not tell today's immigrants what we told the massive waves of immigrants who came here around the turn of the century? Don't come here looking for a handout; you'd better have someone willing to sponsor you if you can't take care of yourself; and be sure to learn English as fast as you can so you can be a productive member of society.

In dollars and sense terms, a significant expansion of legal immigration is simply in our nation's best interest. That's because without immigrants, the U.S. population will soon start to shrink just as the populations of Europe, Russia, and Japan are now shrinking. Without an ever-growing population, we have no hope of delivering on today's social security and medicare promises. If we shut the door on immigrants we will be cutting off our own nose to spite our face.

The second biggest mistake the Republicans are making is with social issues.

Libertarians are the conscience of the Republican Party, and libertarian philosophy tells us that the government that governs the least is the best. Why, if Republicans are all for individual freedom and free markets, are they also calling for national rules governing abortion and gay marriage? Why should the government give me free rein when it comes to working, but stick its nose in my bedroom?

The only sensible approach to social issues is this: they are not within the purview of the federal government. Perhaps they are issues best left to the states, or perhaps they are simply matters of conscience and morality. Personally, I am against abortion, but I'm understanding of the girl who was raped and can't abide the thought of having a baby whose father violated her. Regardless, I don't see why the federal government has a say in the matter or why federal money should be used to fund her abortion.

The third issue that is entirely missing from the debates so far is this: Should the federal government undertake works of charity? Liberals love to feel compassion for the downtrodden and the unfortunate, but when they create government programs to take care of these people, they are doing charitable works with other people's money. That's not charity, that's theft, and it's immoral. Charity is using one's own money to help the downtrodden and the unfortunate. Americans are famously charitable, and I'm convinced that there is no shortage of charitable funds in this country to deal with those who have truly suffered from bad luck or bad genes. There would be even more money available for private charity if we cancelled a good portion of the transfer payments that today represent well over half of total federal spending. Charity should be in the exclusive purview of individuals and the private sector.

In this same vein, it makes no sense for the federal government to design and administer a national healthcare system: that is better left to the private sector. A few simple changes would do wonders toward reforming healthcare: change the tax code to eliminate the huge incentive for employers to pay for employees' insurance, since that will give individuals responsibility for their own healthcare decisions; change the rules to allow insurance companies to offer policies across state lines; and stop governments at all levels from mandating levels and types of coverage. In general, anything that decentralizes decision making, gives individuals the responsibility for paying for their own healthcare costs, and opens the door to competition and market-based innovation is a good idea.

Finally, not only is government "charity" immoral (because it appropriates one person's money to pay for another person's idea of what is right), it is inefficient and destructive of the very fabric of society. When the government tries to take care of our every misfortune, we cease taking responsibility for ourselves and our loved ones. As Milton Friedman taught us years ago, you spend your own money on yourself much more carefully and thoughtfully than you would spend other people's money on other people. We need to get the incentives right, because today they are all screwed up.

Obama has defined the liberal position in no uncertain terms: There is no way we can make any significant cuts in current and projected spending; to close the deficit we will need more taxes, and only the rich can afford to play that role. Meanwhile, we can grow the economy by giving the government more opportunities to direct the course of the economy.

The Republicans are making the exact opposite point: There is no way we can allow the government to remain as big as it is (close to a post-war high relative to GDP), and there is no way we can impose higher tax rates on this economy; to close the deficit we will need to reduce the size and role of government. We can grow the economy by relying less on government to make decisions for us, and more on individuals and free markets to make the right choices.

If you believe that government can administer the economy's scarce resources better than the private sector, vote Democrat. If you believe the private sector administers those scarce resources better than government bureaucrats, vote Republican.

So far, so good, but the Republicans are making three huge mistakes.

The biggest mistake the Republicans are making is on the subject of immigration. The party is veering far too much in the direction of isolationism, and the party is much too anti-immigrant for my taste.

This country was built by immigrants. I believe the vast majority of immigrants are people who are willing to risk everything in the hopes of creating a better life for themselves and their family in a place they've never been. Immigrants bring new blood into the country, new ambition, and yes, they compete with legal residents for jobs. But prosperity is not a zero-sum game. We can have more immigration and more jobs for everyone, if we have the right fiscal and monetary policies and if government gets out of the way of the private sector.

Why do we have so many illegal immigrants? So far, the only answer I've heard is that the federal government has failed to secure our borders. We have failed to keep out the people who desperately want to get in, to find work, and to improve their lives. So, according to most of the candidates, we need to build a bigger fence and devote more resources to policing the border.

I haven't heard anyone say that maybe we unwittingly have created huge, perverse incentives for immigrants to come, because we have a huge social safety net that is not too hard for anyone (including legal residents) to game. Build it and they will come; offer generous handouts and subsidies, and don't be surprised if all sorts of legal and illegal people sign up for a piece of the action.

I haven't heard anyone say that maybe we have so many illegal immigrants because we are making it extremely difficult for those who want to come here, to come legally. We have an immigrant quota system of roughly 500,000 per year, but many more than that want to come. I personally know several people who have waited 5 to 10 years to get a resident visa, because the countries they came from had huge waiting lists. Would you be willing to wait 10 years to take your family to America if you were suffering and willing to work hard?

One solution to our immigration problem would be to drastically increase our annual quotas, especially for those who are offered a job here by an existing business. As it is, work visas are extremely limited in number, and are often allotted in a matter of days, leaving businesses who want to hire a foreigner (perhaps one educated at our excellent universities) in the lurch for the rest of the year.

Another solution to the immigration problem would be to reduce the size of our social safety net. Fewer handouts and fewer subsidies would reduce the incentive to come for those who just want to take advantage of our generosity. Why not tell today's immigrants what we told the massive waves of immigrants who came here around the turn of the century? Don't come here looking for a handout; you'd better have someone willing to sponsor you if you can't take care of yourself; and be sure to learn English as fast as you can so you can be a productive member of society.

In dollars and sense terms, a significant expansion of legal immigration is simply in our nation's best interest. That's because without immigrants, the U.S. population will soon start to shrink just as the populations of Europe, Russia, and Japan are now shrinking. Without an ever-growing population, we have no hope of delivering on today's social security and medicare promises. If we shut the door on immigrants we will be cutting off our own nose to spite our face.

The second biggest mistake the Republicans are making is with social issues.

Libertarians are the conscience of the Republican Party, and libertarian philosophy tells us that the government that governs the least is the best. Why, if Republicans are all for individual freedom and free markets, are they also calling for national rules governing abortion and gay marriage? Why should the government give me free rein when it comes to working, but stick its nose in my bedroom?

The only sensible approach to social issues is this: they are not within the purview of the federal government. Perhaps they are issues best left to the states, or perhaps they are simply matters of conscience and morality. Personally, I am against abortion, but I'm understanding of the girl who was raped and can't abide the thought of having a baby whose father violated her. Regardless, I don't see why the federal government has a say in the matter or why federal money should be used to fund her abortion.

The third issue that is entirely missing from the debates so far is this: Should the federal government undertake works of charity? Liberals love to feel compassion for the downtrodden and the unfortunate, but when they create government programs to take care of these people, they are doing charitable works with other people's money. That's not charity, that's theft, and it's immoral. Charity is using one's own money to help the downtrodden and the unfortunate. Americans are famously charitable, and I'm convinced that there is no shortage of charitable funds in this country to deal with those who have truly suffered from bad luck or bad genes. There would be even more money available for private charity if we cancelled a good portion of the transfer payments that today represent well over half of total federal spending. Charity should be in the exclusive purview of individuals and the private sector.

In this same vein, it makes no sense for the federal government to design and administer a national healthcare system: that is better left to the private sector. A few simple changes would do wonders toward reforming healthcare: change the tax code to eliminate the huge incentive for employers to pay for employees' insurance, since that will give individuals responsibility for their own healthcare decisions; change the rules to allow insurance companies to offer policies across state lines; and stop governments at all levels from mandating levels and types of coverage. In general, anything that decentralizes decision making, gives individuals the responsibility for paying for their own healthcare costs, and opens the door to competition and market-based innovation is a good idea.

Finally, not only is government "charity" immoral (because it appropriates one person's money to pay for another person's idea of what is right), it is inefficient and destructive of the very fabric of society. When the government tries to take care of our every misfortune, we cease taking responsibility for ourselves and our loved ones. As Milton Friedman taught us years ago, you spend your own money on yourself much more carefully and thoughtfully than you would spend other people's money on other people. We need to get the incentives right, because today they are all screwed up.

It's still all about Europe

The market's wild reaction to the FOMC's announcement yesterday (gold down, dollar up, euro down, T-note and T-bond yields down, equities down, commodities down) begs an attempt to diagnose what is going on. One explanation that seems to make sense is that what the market was really looking for from the FOMC was a QE3, not an Operation Twist 2. Increasing the duration of the Fed's Treasury holdings doesn't do much of anything for the economy, but deciding to no longer pay interest on excess reserves, for example, would have been a clear move to an easier policy stance, and that might have relieved some of the pressures in Europe, or at least so the thinking goes. By not announcing a true easing of monetary policy, the FOMC's announcement could thus have sparked fears that the deterioration in Europe was increasingly likely to result in some sort of economic destruction.

So here's my guess as to mindset behind the market moves these past several days: The market's desire for Treasury bonds has gone way up because there is huge demand for a safe asset that still pays interest and is assured of having a buyer for the next 10 months. Plus, as indicated in my previous post, the mortgage market's negative convexity is adding significantly to the market's desire for duration, thus accentuating the decline in Treasury yields. The demand for euros fell because Europe is now seen to be in worse trouble—not even the Fed can help, and the dollar is the only safe-haven that is still cheap. Gold wasn't favored because if the Eurozone economy collapses, then inflation is more likely to go down than up (recall that gold fell in the second half of 2008); this message is also seen in the 30 bps drop in forward breakeven inflation spreads since last week.

Equities everywhere are down because the market fears that a Greek default is imminent and it will be contagious and that could result in a global financial crisis and/or a global economic slump similar to what followed in the wake of the Lehman collapse in 2008. Commodities are down because of the widespread fear that a global economic slump/collapse is just around the corner, and because speculators everywhere have been burned by huge volatility.

At the core of all these concerns is Eurozone sovereign debt default risk, as I noted here and here.

To balance these fears, and to flesh out some of the price action, consider the following updated charts:

Since late 2009, the number of U.S. persons receiving unemployment insurance (above chart) has dropped by 5.2 million, or more than half (i.e., down 55% from a peak of 11.5 million). Over this same period, the unemployment rate has declined from 10.1% in Oct. '09 to 9.1% today. Fewer people being supported by unemployment insurance equals more people with a greater incentive to find and accept a job. In the end, that is a good thing.

Over that same time frame, the number of new claims for unemployment insurance has been falling steadily. On an unadjusted basis (see chart above), new claims were only 350K in the week ending Sept 16th, down from 382K in the same week last year. There is no sign here of any imminent or emerging collapse in the U.S. economy or the jobs market.

On a seasonally-adjusted and smoothed basis, the trend in weekly claims appears to still be declining. Recessions are always preceded by a substantial increase in claims, but that is manifestly not the case today.

The index of Leading Indicators continues to rise, up 6.5% over the past year. Every recession for the past 50 years has been preceded by a significant decline in the growth rate of this index; that is not the case today. To be sure, this index is not always a good leading indicator, but it is not even close to signaling impending doom or even a modest recession.

The behavior of swap spreads—excellent leading indicators of systemic risk—is the clearest indicator that it is Europe that is facing the big problems. There is now a huge and unprecedented divergence between U.S. and Eurozone swap spreads. Systemic risk in the U.S. remains within a "normal" range, but eurozone swap spreads are over 100 bps, a sure sign of imminent and painful problems there.

The dollar has been the main beneficiary of the recent panic crisis, but it is still quite low from an historical perspective. It's recent strength derives mainly from the new-found weakness in the euro, not from any effective tightening on the part of the Fed. Maybe a QE3 could have helped Europe, but that is far from obvious, and in any event there are no other signs that dollars are in short supply relative to demand.

The most recent data on residential and commercial property prices (June and July, respectively) shows that prices have been roughly flat for the past two and a half years. The bursting of the commercial property price "bubble" is quite obvious here, but now that it has burst, prices are no longer declining.

The recent plunge in copper prices is typical of many commodities: very painful, but not by any means unprecedented, and prices are still quite elevated from an historical perspective. Speculators of all stripes have been burned in many ways with all the volatility sweeping the markets these days. It's not surprising that commodity prices have corrected.

Gold has suffered a nasty, $180 decline from its recent, all-time high, but from a long-term perspective it looks like a simple correction. Gold only got as high as it is because it has been pricing in lots of devastating news; this recent decline could be an indication that although the recent news has sparked a panic in bond and equity markets, it's not as bad as gold investors had expected.

To date, the drop in the S&P 500 from its recent highs has been about 15%. Prices are still almost 70% above the Mar. '09 lows. It's a panic, to be sure, but not nearly a collapse. Corporate profits have doubled from their year-end 2008 lows, the average PE ratio is only 12.3, according to my Bloomberg, and those facts provide a strong safety net for prices.

Taking everything into consideration, it's quite apparent that the source of the recent angst is the increasing likelihood of a major sovereign default (e.g., Greece), and the fear that this might prove contagious and eventually escalate to the level of a global financial and economic panic. There's no denying that Greece is almost certainly going to default, and that it will be the biggest sovereign default on record. Whether that is big enough to bring down the entire world is the question at hand. I just don't see it.

Mortgage market panic adds to market distortions

10-yr Treasury yields have never been as low as they are today (1.73% as of this writing). Meanwhile, the effective duration of the MBS market has rarely been lower. The two go hand in hand, since the huge collapse in the duration of MBS (from a high of 4.9 years last April to just 1.5 today, by my estimates) has forced large institutional money managers to buy huge amounts of Treasury notes and bonds in order to keep the duration of their portfolios from collapsing, otherwise they would suffer significant underperformance. Declining MBS duration, in other words, has contributed significantly to the decline in Treasury yields.

The combination today of record-low Treasury yields and almost-record-low MBS duration is like compressing a massive spring: if and when the downward pressure on yields lets up, we will see a massive rebound in yields as the recent process reverses. Managers would be forced to sell massive amounts of Treasury notes and bonds in order to offset the huge increases in MBS duration that will follow any rise in Treasury yields. Thus it is that the mortgage market, which comprises about 28% of the investment grade U.S. bond market, can sometimes be the tail that wags the much larger dog—magnifying greatly the market's underlying volatility during periods of stress. Just a modest nudge from the Fed, in the form of the upcoming Operation Twist, can result—at least temporarily—in a huge decline in yields. And just a whiff of good news could send yields sharply higher. We have seen big reversals before when similar conditions existed (i.e., a big decline in 10-yr yields and a big drop in MBS duration): last Fall, early 2009, the Summer of 2003, and early 1999. The next one could be the mother of all Treasury meltdowns.

The only way that a big increase in yields can be avoided is if the downward pressure on Treasury yields continues. And that can only happen if the economy enters another profound recession, and/or inflation turns negative. Once again we find ourselves on the edge of the same abyss we were staring into at the end of 2008: this market is priced to something akin to the-end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it; nothing less than a catastrophic deterioration from current conditions. No one can rule out a truly worst-case scenario, but to get there requires a whole host of things to go from today's unpleasant to absolutely abysmal. I'm not prepared to bet that the bottom will fall out of everything, so that leaves me bullish compared to where the market is.

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Rents vs. housing prices

I've seen a lot of talk lately about how the CPI is way over-stating inflation, since its largest component—owner's equivalent rent—has increased over 7% since the end of 2006. Housing has contributed to inflation? How can that be if we all know that home prices have collapsed. Ha, ha.

The chart above helps to understand what is really going on. Due to the extreme volatility of housing prices in the 1970s, in the BLS decided in the early 1980s to switch from using home prices as an input to the CPI to instead using "rents," since they don't tend to change as much. This decision remains controversial, but as the chart shows, rents (which are estimated) have been much more stable than prices, and over time the two have tracked pretty well. If the CPI is overstating inflation today because it uses rents instead of prices, then it was hugely understating inflation in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Regardless of whether you had used housing prices as an input to the CPI, or rents, by now the cumulative amount of inflation you get is roughly the same. The difference between prices and rents evens out over time, which stands to reason.

This chart uses all the available data from Case Shiller, and that data only includes the prices of the 10 largest metropolitan markets, so the fact that prices have increased about 16% more than rents since 1987 is not to be given too much importance. The important thing is to see how the two series track each other over time. It's my understanding that rents today (which are widely reported to be rising) are becoming expensive relative to the cost of purchasing a house. So an ideal version of this chart might show that owner's equivalent rents have risen more than housing prices over the past several decades. But in any case, it disproves the allegation that the BLS is mis-reporting inflation. Rents and housing prices have come back into line, after a period in which housing prices were grossly inflated.

Operation Twist is over-hyped

With 10-yr Treasury yields trading at historic, record lows, we need lower yields to stimulate the economy?

As we wait to hear from the FOMC regarding whether they will embrace the much-hyped Operation Twist strategy, I have to believe that the market will be disappointed. For my money, 10-yr yields are as low as they need to go already. Either the Fed will not embark on a new "twist" strategy, or they will do it in a very modest fashion to show that they are concerned about the economy, but it won't make much, if any difference, to the monetary policy fundamentals.

UPDATE: The FOMC announced a shift in its existing holdings which involves the sale of $400 billion of securities of 5 years maturity and less, coupled with the purchase of $400 billion of securities with maturities of 6 to 30 years, and a decision to reinvest principal payments from existing MBS in new MBS. Thus there will be no material expansion of the Fed's balance sheet. This leaves the major thrust of monetary policy intact, while fiddling around the edges with the yield curve. Given the existing extremely low level of longer-term Treasury yields, I don't see that this policy announcement will have much impact on the overall health of the financial market or the economy.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)