Today's revision to the first quarter GDP report didn't contain any new news. The stock market is still (uncomfortably for many who worry that falls typically follow rises) near its all-time highs, both nominally and in real terms, and Treasury yields are still close to their all-time lows. It's a mixed bag, full of worry and caution.

The relatively small decline in first quarter GDP is hardly more than a blip on the long-term chart (above).

Over the past two years, GDP has grown at an annualized pace of about 2.4%, which is the same rate of growth that has prevailed for the duration of the current expansion. Nothing has changed. The real yield on 5-yr TIPS is priced to continued weak economic growth.

Weak quarters happen every now and then. They don't necessarily precede recessions, nor do they make recessions more likely. It's quite likely that growth will bounce back in the current quarter—such are the vagaries of GDP accounting.

After-tax corporate profits continue to grow, and they remain very strong relative to GDP. Yet PE ratios are only moderately above their long-term average. This suggests the market is still very skeptical that profits can continue to rise.

Both the National Income and Products Accounts and the reported earnings of the S&P 500 appear to be growing at about the same pace. By both measures, profits are at an all-time high.

Using NIPA after-tax corporate profits as the "E" and the S&P 500 index as the "P", PE ratios are moderately above their long-term average. Nothing unusual at all about this. The market was quite exuberant in 2000 by this measure, but is still relatively cautious today—considering how strong profits are relative to GDP.

Blogging may be light for the next week or so, as we are embarking on a trip to Italy in a few hours.

Friday, May 29, 2015

Tuesday, May 26, 2015

Housing still a bright spot in an otherwise dull economy

According to the BEA's first estimate, the economy grew at a miserable 0.2% annualized rate in the first quarter of this year. The current consensus of opinion holds that this will be revised down to -0.9%. However, we've seen this movie before (e.g., last year's first quarter growth was miserable too), and what happens is that growth bounces back in the second quarter. The GDP numbers are notoriously volatile, much more so than the actual economy, which has considerable "momentum."

Most of the data I've seen over the past few months suggests that the economy continues to grow at a relatively slow pace. Most importantly, there are none of the classical warning signs of deterioration. Swap spreads continue to be very low and relatively stable. Credit spreads are relatively low, and have come down somewhat from their January highs—most of the damage in the credit sector has occurred in the energy and oil-related space, and even there spreads have tightened in recent months. Monetary policy continues to be accommodative, and the nominal and real yield curves are still positively sloped. Real borrowing costs are very low or negative for most borrowers. Commodity prices are down on the margin, but are still much higher (about 40% higher) than they were a decade ago. Fiscal policy could be much more pro-growth, but it's quite unlikely to take a turn for the worst; in fact, it's not unreasonable to think that tax and regulatory burdens are more likely to ease in the future than increase.

One notable exception, however, is the recent trend in cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco to jack up minimum wages. This is like slapping small businesses with a big new tax, as Mark Perry points out, and that is very likely to hurt growth in the affected local economies. The economic ignorance and willingness to pander of politicians apparently knows no bounds. As a reminder, I noted a few months ago that only about 1% of those who work actually earn minimum wage or less. The ones hurt the most from higher minimum wages will be the young and the poor who find that it's much harder to find that first job. The vast majority of workers—and the lion's share of the economy—will not be much affected.

Today's economic releases show that the housing market continues to recover at a fairly impressive pace. According to Case-Shiller, U.S. home prices are up over 30% since early 2012, and are only 13% below their all-time highs of 2005. In real terms, prices are still about 25% below their 2006 highs, so we're likely years away from another housing "bubble." Meanwhile, April New Home Sales were up a very strong 26% from year-ago levels.

Charts and commentary follow:

The two charts above show the nominal and real level of housing prices as measured by Case-Shiller. Both show that prices have been moving steadily higher for more than three years.

As the chart above suggests, the ongoing rise in home prices (which are up 4.7% in the past year), is likely to contribute positively to the CPI over the next year or so. Higher home prices mean higher future rents, and rents make up about 25% of the CPI.

April New Home Sales were stronger than expected (517K vs. 508K), and were 26% above year-ago levels. There is still plenty of upside potential here.

April Capital Goods Orders were also stronger than expected (+1.0% vs. +0.3%), but they remain quite sluggish. I prefer to look at a 3-mo. moving average of capex, and by that measure orders were on the weak side and haven't increased at all since early last year. In real terms, capex hasn't increased at all for the past two decades! This is the least impressive part of the economy, since it reflects a dearth of business investment, and that limits the economy's future potential growth. As a consequence, while it's quite likely that GDP growth will be much stronger in the second quarter than it was in the first, that won't change the underlying fundamentals, which continue to point to growth of roughly 2-3%, with a large (about 10%) and growing "output gap" that I estimate to be about $2 trillion.

Friday, May 22, 2015

Treasury yields are very low relative to inflation

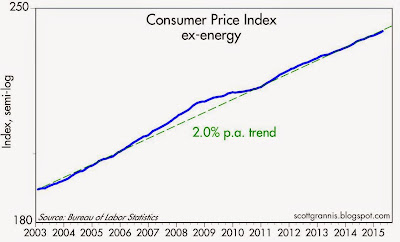

Volatile oil prices have distorted the Consumer Price Index; removing them reveals that inflation has been running at a relatively stable 2% rate for the past 12 years. No one—especially the Fed—needs to worry that inflation is too low. If anything is too low, it is Treasury yields.

The chart above plots the CPI index ex-energy on a semi-log scale to show that it has been increasing at a 2% annual rate, on average, since 2003. There is no indication at all that the underlying rate of inflation today is any more or less than it has been for over a decade. For all intents and purposes, inflation is only slightly less than 2%, which is precisely what the Fed has been aiming for.

The chart above compares the year over year change in the Core CPI to 5-yr Treasury yields. Yields tracked inflation trends fairly closely from 2003 through early 2011. Beginning around mid-2011, the PIIGS crisis began to erupt, pushing the Eurozone economy into a recession, which in turn raised concerns that the U.S. economy was vulnerable to a double-dip recession as well. Strong demand for the safety of Treasuries, fueled by risk aversion, has kept sovereign interest rates abnormally low—relative to underlying inflation—for the past four years.

Fears of a Eurozone credit crisis sparking another financial collapse also drove gold prices to $1900 in September, 2011, while strong demand for the safety of 5-yr TIPS drove real yields deep into negative territory. The world was terribly concerned that economic growth was going to be miserable and financial markets were at risk. Demand for the safety and security of gold, Treasuries, and TIPS was intense. As the chart above shows, demand for gold and TIPS eased measurably in 2013, but remains relatively strong: risk aversion has eased somewhat but it is still very much with us today.

The chart above shows the real yield on 10-yr Treasuries (using the Core measure of CPI) since 1960, during which time real yields by this measure have averaged 2.4%. Today's level of real Treasury yields is clearly abnormally low from a long-term historical perspective. The reason for this, I believe, is the persistence of risk aversion and an enduring skepticism about the prospects for economic growth.

If economic policies were to become more growth-oriented, and if regulatory burdens were to decline, it's reasonable to think that Treasury yields could almost immediately rise by 150-200 bps or so, thus restoring real yields to more historically "normal" levels.

As the chart above shows, the year over year change in the headline CPI has been unusually volatile in the past decade. Core inflation (ex-foor and energy) has been much more stable. The main difference between these two measures of inflation is oil prices.

The chart above plots the CPI index ex-energy on a semi-log scale to show that it has been increasing at a 2% annual rate, on average, since 2003. There is no indication at all that the underlying rate of inflation today is any more or less than it has been for over a decade. For all intents and purposes, inflation is only slightly less than 2%, which is precisely what the Fed has been aiming for.

The chart above compares the year over year change in the Core CPI to 5-yr Treasury yields. Yields tracked inflation trends fairly closely from 2003 through early 2011. Beginning around mid-2011, the PIIGS crisis began to erupt, pushing the Eurozone economy into a recession, which in turn raised concerns that the U.S. economy was vulnerable to a double-dip recession as well. Strong demand for the safety of Treasuries, fueled by risk aversion, has kept sovereign interest rates abnormally low—relative to underlying inflation—for the past four years.

Fears of a Eurozone credit crisis sparking another financial collapse also drove gold prices to $1900 in September, 2011, while strong demand for the safety of 5-yr TIPS drove real yields deep into negative territory. The world was terribly concerned that economic growth was going to be miserable and financial markets were at risk. Demand for the safety and security of gold, Treasuries, and TIPS was intense. As the chart above shows, demand for gold and TIPS eased measurably in 2013, but remains relatively strong: risk aversion has eased somewhat but it is still very much with us today.

The chart above shows the real yield on 10-yr Treasuries (using the Core measure of CPI) since 1960, during which time real yields by this measure have averaged 2.4%. Today's level of real Treasury yields is clearly abnormally low from a long-term historical perspective. The reason for this, I believe, is the persistence of risk aversion and an enduring skepticism about the prospects for economic growth.

If economic policies were to become more growth-oriented, and if regulatory burdens were to decline, it's reasonable to think that Treasury yields could almost immediately rise by 150-200 bps or so, thus restoring real yields to more historically "normal" levels.

Thursday, May 21, 2015

Claims keep falling, but risk aversion is still the problem

This continues to be the weakest recovery in modern times, but it has set a record for the lowest rate of layoffs.

Relative to the number of people working, claims are now at their lowest point in recorded history. The average worker has never been so little at risk of losing his or her job.

Meanwhile, after-tax corporate profits have never been so strong.

Nevertheless, despite record-setting profits, business investment has been quite weak. In real terms, capital goods orders, a good proxy for business investment, are at the same level today as they were 20 years ago, even though the economy has grown by over 60% in that time!

The problem today is not layoffs and unemployment, it's a lack of investment. Animal spirits are lacking, and risk aversion is still high.

Sovereign yields in developed countries are very near their all-time lows. That is the best proof that animal spirits are lacking and risk aversion is still high. The world is willing to pay extraordinarily high prices for the safety and security of sovereign debt. Why? Because the world is very afraid of the alternatives, even though they yield substantially more.

As the chart above shows, the earnings yield on the S&P 500 has rarely been so high relative to the yield on 10-yr Treasuries.

Weak investment and tepid jobs growth have created a $2 trillion annual shortfall in GDP (by my calculations, the so-called output gap is about 10% of GDP).

Even a massive increase in government spending and transfer payments couldn't boost the economy. Indeed, it's quite likely that it was the big increase in government spending and transfer payments that weakened the economy.

The solution to this dilemma is straightforward. We don't need more attempts at government stimulus. What we desperately need is more incentives for private investment. We need lower marginal tax rates and we need reduced regulatory burdens.

Using a 4-week moving average, initial claims for unemployment last week fell to their lowest level in 15 years.

Relative to the number of people working, claims are now at their lowest point in recorded history. The average worker has never been so little at risk of losing his or her job.

Meanwhile, after-tax corporate profits have never been so strong.

Nevertheless, despite record-setting profits, business investment has been quite weak. In real terms, capital goods orders, a good proxy for business investment, are at the same level today as they were 20 years ago, even though the economy has grown by over 60% in that time!

The problem today is not layoffs and unemployment, it's a lack of investment. Animal spirits are lacking, and risk aversion is still high.

Sovereign yields in developed countries are very near their all-time lows. That is the best proof that animal spirits are lacking and risk aversion is still high. The world is willing to pay extraordinarily high prices for the safety and security of sovereign debt. Why? Because the world is very afraid of the alternatives, even though they yield substantially more.

As the chart above shows, the earnings yield on the S&P 500 has rarely been so high relative to the yield on 10-yr Treasuries.

Weak investment and tepid jobs growth have created a $2 trillion annual shortfall in GDP (by my calculations, the so-called output gap is about 10% of GDP).

Even a massive increase in government spending and transfer payments couldn't boost the economy. Indeed, it's quite likely that it was the big increase in government spending and transfer payments that weakened the economy.

The solution to this dilemma is straightforward. We don't need more attempts at government stimulus. What we desperately need is more incentives for private investment. We need lower marginal tax rates and we need reduced regulatory burdens.

Tuesday, May 19, 2015

Housing market still improving

April housing starts rose almost 12% more than expected (1135K vs. 1015K), reaching a new post-recession high. This shouldn't have been too surprising, given the relatively strong readings of builder sentiment, as the chart above suggests. Housing starts are still only half what they were at the height of the boom, so it's reasonable to think that the housing recovery is still a long way from exhausting itself. We're likely to see slow but steady growth for years to come.

The housing recovery is also reflected in home prices, which are still comfortably below their 2005-2006 highs, both in nominal and real terms.

Mortgage rates are still very low from an historical perspective, adding significantly to housing affordability. Higher rates seem almost inevitable at this point, and that is likely to fuel housing demand as buyers rush to catch the train before it leaves the station.

Real yields on 5-yr TIPS (blue line in the chart above) are one of my favorite indicators, since they speak volumes about the bond market's sense of how strong the economy is. They have jumped some 170 bps in just over two years, and they are comfortably above the real yield on Fed funds. This suggests that the economy's growth fundamentals have improved substantially even as Fed policy remains accommodative. Nothing scary about this picture; expect more of the same in the months to come.

Friday, May 15, 2015

Oil prices rise, consumer confidence drops

As the chart above shows, the price of regular gasoline at the pump has rebounded about 30% in the past 3 ½ months, after dropping by almost half since last summer.

As the chart above shows, this has dampened consumers' enthusiasm a bit. Nevertheless, consumer confidence is still fairly close to its post-recession highs.

As the chart above shows, active oil and gas drilling rigs in the U.S. have plunged in response to the collapse in oil prices. But the decline in the rig count is slowing down, and this means that supply and demand are coming back into balance. The bounce in oil and gas prices may be a bit overdone (markets have a way of over-reacting), but nevertheless it's quite likely that gasoline prices will be substantially lower going forward than they have been in the recent past, and that augurs well for things in general. Energy is what makes the world go 'round, so cheaper energy should eventually translate into healthier economic growth.

Thursday, May 14, 2015

No deflation in the PPI

The April Producer Price Indices saw a lot of negative numbers (e.g., final demand -0.4% for the month, -1.3% for the year), but it's all due to falling energy prices. When there are huge swings in oil prices such as we've seen in the past year or so, it's entirely appropriate to focus on core measures (ex food and energy) of inflation. Doing so shows us that at the producer level, inflation has been running at about 2% a year for the past several years.

The chart above focuses on the total and core measures of the traditional version of the PPI (in recent years the BLS has begun releasing a new version called "final demand" which show inflation by both measures to be lower, but I'm sticking with the "finished goods" version that goes back decades for its historical value). Here we see how oil prices have introduced a huge amount of volatility to the total PPI. We also see that the core PPI has been running around 2% for quite some time. In fact, over the past 20 years, the annualized rate of increase in the core PPI has been 1.6%. We're not in some "new normal" world—when it comes to inflation, nothing much has changed for the past two decades.

The chart above subtracts the core PPI from the yield on 10-yr Treasuries. Here we seen that real interest rates today are back to the levels of the late 1970s. There has been a steady decline in real interest rates ever since the early 1980s. When real interest rates are zero or less, using leverage to buy things begins to become very attractive. It's not surprising therefore that there is a growing body of evidence that bank lending is picking up.

As the chart above shows, the growth of bank credit has been accelerating since early last year. Over the past six months, Total Bank Credit is up at a 10% annualized pace.

Now is not the time to worry about deflation. The Fed should begin to normalize interest rates to avoid excessive borrowing and rising inflation.

The chart above focuses on the total and core measures of the traditional version of the PPI (in recent years the BLS has begun releasing a new version called "final demand" which show inflation by both measures to be lower, but I'm sticking with the "finished goods" version that goes back decades for its historical value). Here we see how oil prices have introduced a huge amount of volatility to the total PPI. We also see that the core PPI has been running around 2% for quite some time. In fact, over the past 20 years, the annualized rate of increase in the core PPI has been 1.6%. We're not in some "new normal" world—when it comes to inflation, nothing much has changed for the past two decades.

The chart above subtracts the core PPI from the yield on 10-yr Treasuries. Here we seen that real interest rates today are back to the levels of the late 1970s. There has been a steady decline in real interest rates ever since the early 1980s. When real interest rates are zero or less, using leverage to buy things begins to become very attractive. It's not surprising therefore that there is a growing body of evidence that bank lending is picking up.

As the chart above shows, the growth of bank credit has been accelerating since early last year. Over the past six months, Total Bank Credit is up at a 10% annualized pace.

Now is not the time to worry about deflation. The Fed should begin to normalize interest rates to avoid excessive borrowing and rising inflation.

Tuesday, May 12, 2015

What equity market bubble?

Ruchir Sharma argues in today's WSJ ("The Federal Reserve Asset Bubble Machine") that the Fed's easy money policies have created dangerous asset market bubbles in "stocks ... bonds, houses and every other financial asset." In particular, he claims that his "composite valuation for the three major financial assets in America—stocks, bonds and houses—is currently well above levels reached during the bubbles of 2000 and 2007."

Although I don't agree that stocks and houses are egregiously overvalued, he is correct to point out that Fed policy is in uncharted waters: "we have analyzed data going back two centuries and found that until the past decade no major central bank had ever before set short-term interest rates at zero, even in periods of deflation." It's also the case that no central bank has ever expanded its balance sheet to the extent the Fed has, and excess reserves in the U.S. banking system are orders of magnitude higher (currently about $2.5 trillion) than they have ever been before. He is also correct when he concedes that it is hard to prove that Fed policy has been inflationary since measured inflation remains quite low.

His beef is with asset market prices, something the Fed has never attempted to control, but which he thinks they should pay attention to, if not worry about.

I do think that bond yields are low enough—relative to core inflation—to be considered "bubbly," but as I've noted for some time now, stocks appear to be trading only modestly above what looks to be fair value, and housing prices are still well below their 2006 highs. Furthermore, if money were so easy that as to be artificially inflating asset prices, I should think the dollar would be very weak, and certainly not trading—as it is—at historically average prices relative to other currencies. On balance, I don't think it's at all obvious that we are in the presence of dangerously inflating asset bubbles in stocks and housing. We may well get there, if the Fed fails to tighten monetary policy in a timely and sufficient manner, but we're not there yet.

What follows are some charts that help back up my assertions:

10-yr Treasury yields—the benchmark for most bonds—are indeed very close to their all-time lows.

But looking at nominal yields in a vacuum can be misleading. It's best to compare nominal yields to inflation, since that gives a much better idea of the true "valuation" of bonds. As the chart above shows, when core CPI inflation is subtracted from 10-yr Treasury yields they are still more than 100 bps above their modern-era lows. But abstracting from the period 2011-2013, real yields haven't been as low as they are today for the past 40 years. I think this qualifies as "bubbly," but to be fair it's also symptomatic of significant risk aversion (i.e., the world is willing to pay very high prices for the safety of Treasuries).

Real home prices are still 25% below their 2006 peak. Meanwhile, 30-yr fixed mortgage rates today are just under 4%, while they were 6% or higher in 2006. Housing is therefore much more affordable today than it was in 2006 or 2007. It could take years for housing to return to the valuations of 2006/2007.

At 18.5, the current PE ratio of the S&P 500 is only moderately higher than its 55-year average. It was far higher in the late 1990s. This could arguably be grounds for thinking that stocks are overvalued.

The chart above compares the earnings yield on stocks to the inverse of the real yield on 5-yr TIPS (which I use as a proxy for their price). Here we see that TIPS are still trading at very high prices, which means that the market is willing to pay a huge premium for the double safety of TIPS (which are default-free and protected against inflation). Earnings yields are also relatively high, which means the market is not very confident that profit margins will continue at current lofty levels. Together, these are symptomatic of a market that does not believe the economy is going to be very strong for the foreseeable future. In other words, this is a market that is still quite risk-averse—not a market that is over-priced.

As the chart above shows, the difference between the earnings yield on stocks and the yield on 10-yr Treasuries (a measure of the equity risk premium) is quite a bit higher than its historic average. If we grant that yields on Treasuries are "bubbly" and should be closer to 4% than to 2%, then the equity risk premium today would be about normal. So in this sense stocks are not over-priced at all; they are priced to the expectation that yields—and discount rates—will be much higher in the future.

The chart above compares the ratio of the S&P 500 to nominal GDP (blue line) to the yield on 10-yr Treasuries. The two tend to track each other, which is reasonable, since profits are a function of nominal GDP and the value of stocks is the present value of future profits discounted by some interest rate. Higher yields go hand in hand with lower valuations, and vice-versa. By this measure, stocks today have about the same valuation as they did in the 1960s, when bond yields were around 4%. In other words, stocks are not being discounted at current interest rates; rather, they are behaving as if interest rates were 4% instead of 2%. This is yet another sign that stocks are not wildly over-valued. (Note how stocks were indeed very overvalued by this measure in the late 1990s.)

If there is one fundamental reason for why the Sharmas of the world worry about over-priced asset markets but I don't, it is because they fail to understand that the Fed hasn't been super-easy. They start by assuming that monetary policy and zero interest rates are highly stimulative, and have been for years, and that therefore asset markets must be overpriced. They believe that monetary inflation can be found in asset prices, and it will eventually show up in the official inflation numbers.

In contrast, I start with the assumption that the Fed has not been stimulative. The Fed has merely accommodated a very strong demand for money, which in turn is a by-product of the huge degree of risk aversion that has been in evidence around world in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. The Fed hasn't printed massive amounts of money, they've only swapped bank reserves for notes and bonds, in an effort to satisfy a risk-averse world.

I've explained this in greater detail in many posts over the past several years, and you can find some here. Quantitative Easing, huge excess reserves, low inflation, a relatively strong dollar and risk-averse markets all fit together, once you understand the Fed hasn't been super-easy. The equity and housing markets are not cheap, but they are not necessarily overpriced: in fact, I think they're still somewhat cautiously priced.

Although I don't agree that stocks and houses are egregiously overvalued, he is correct to point out that Fed policy is in uncharted waters: "we have analyzed data going back two centuries and found that until the past decade no major central bank had ever before set short-term interest rates at zero, even in periods of deflation." It's also the case that no central bank has ever expanded its balance sheet to the extent the Fed has, and excess reserves in the U.S. banking system are orders of magnitude higher (currently about $2.5 trillion) than they have ever been before. He is also correct when he concedes that it is hard to prove that Fed policy has been inflationary since measured inflation remains quite low.

His beef is with asset market prices, something the Fed has never attempted to control, but which he thinks they should pay attention to, if not worry about.

I do think that bond yields are low enough—relative to core inflation—to be considered "bubbly," but as I've noted for some time now, stocks appear to be trading only modestly above what looks to be fair value, and housing prices are still well below their 2006 highs. Furthermore, if money were so easy that as to be artificially inflating asset prices, I should think the dollar would be very weak, and certainly not trading—as it is—at historically average prices relative to other currencies. On balance, I don't think it's at all obvious that we are in the presence of dangerously inflating asset bubbles in stocks and housing. We may well get there, if the Fed fails to tighten monetary policy in a timely and sufficient manner, but we're not there yet.

What follows are some charts that help back up my assertions:

10-yr Treasury yields—the benchmark for most bonds—are indeed very close to their all-time lows.

But looking at nominal yields in a vacuum can be misleading. It's best to compare nominal yields to inflation, since that gives a much better idea of the true "valuation" of bonds. As the chart above shows, when core CPI inflation is subtracted from 10-yr Treasury yields they are still more than 100 bps above their modern-era lows. But abstracting from the period 2011-2013, real yields haven't been as low as they are today for the past 40 years. I think this qualifies as "bubbly," but to be fair it's also symptomatic of significant risk aversion (i.e., the world is willing to pay very high prices for the safety of Treasuries).

Real home prices are still 25% below their 2006 peak. Meanwhile, 30-yr fixed mortgage rates today are just under 4%, while they were 6% or higher in 2006. Housing is therefore much more affordable today than it was in 2006 or 2007. It could take years for housing to return to the valuations of 2006/2007.

At 18.5, the current PE ratio of the S&P 500 is only moderately higher than its 55-year average. It was far higher in the late 1990s. This could arguably be grounds for thinking that stocks are overvalued.

However, as the chart above shows, after-tax corporate profits have been running at record levels relative to GDP for the past several years. Profit margins, in other words, are at record levels and have been for some time now. Why shouldn't PE ratios be trading a bit rich considering how strong profits have been?

The chart above compares the earnings yield on stocks to the inverse of the real yield on 5-yr TIPS (which I use as a proxy for their price). Here we see that TIPS are still trading at very high prices, which means that the market is willing to pay a huge premium for the double safety of TIPS (which are default-free and protected against inflation). Earnings yields are also relatively high, which means the market is not very confident that profit margins will continue at current lofty levels. Together, these are symptomatic of a market that does not believe the economy is going to be very strong for the foreseeable future. In other words, this is a market that is still quite risk-averse—not a market that is over-priced.

As the chart above shows, the difference between the earnings yield on stocks and the yield on 10-yr Treasuries (a measure of the equity risk premium) is quite a bit higher than its historic average. If we grant that yields on Treasuries are "bubbly" and should be closer to 4% than to 2%, then the equity risk premium today would be about normal. So in this sense stocks are not over-priced at all; they are priced to the expectation that yields—and discount rates—will be much higher in the future.

The chart above compares the ratio of the S&P 500 to nominal GDP (blue line) to the yield on 10-yr Treasuries. The two tend to track each other, which is reasonable, since profits are a function of nominal GDP and the value of stocks is the present value of future profits discounted by some interest rate. Higher yields go hand in hand with lower valuations, and vice-versa. By this measure, stocks today have about the same valuation as they did in the 1960s, when bond yields were around 4%. In other words, stocks are not being discounted at current interest rates; rather, they are behaving as if interest rates were 4% instead of 2%. This is yet another sign that stocks are not wildly over-valued. (Note how stocks were indeed very overvalued by this measure in the late 1990s.)

If there is one fundamental reason for why the Sharmas of the world worry about over-priced asset markets but I don't, it is because they fail to understand that the Fed hasn't been super-easy. They start by assuming that monetary policy and zero interest rates are highly stimulative, and have been for years, and that therefore asset markets must be overpriced. They believe that monetary inflation can be found in asset prices, and it will eventually show up in the official inflation numbers.

In contrast, I start with the assumption that the Fed has not been stimulative. The Fed has merely accommodated a very strong demand for money, which in turn is a by-product of the huge degree of risk aversion that has been in evidence around world in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. The Fed hasn't printed massive amounts of money, they've only swapped bank reserves for notes and bonds, in an effort to satisfy a risk-averse world.

I've explained this in greater detail in many posts over the past several years, and you can find some here. Quantitative Easing, huge excess reserves, low inflation, a relatively strong dollar and risk-averse markets all fit together, once you understand the Fed hasn't been super-easy. The equity and housing markets are not cheap, but they are not necessarily overpriced: in fact, I think they're still somewhat cautiously priced.

Friday, May 8, 2015

A decent April jobs report

The April jobs report was widely viewed as pushing the Fed's "liftoff" at least several months into the future. Although it came in close to expectations (223K vs. 228K), downward revisions to February and March dampened enthusiasm. But that's old news—we knew the economy was weak in the first quarter. What counts is that jobs growth has bounced back and the economy is not sinking: the slump is behind us, as I noted earlier this week. So on balance I think this was a decent report.

Jobs growth bounced back in April, following a slump in March, much as I anticipated. We'll probably see a stronger report next month. These things happen; what's important is that the economy's fundamentals haven't changed. It's still the slowest recovery on record, but the economy does continue to expand.

The current pace of jobs growth is within a range of 2 - 2.5%, which is very much in line with what we have seen the past several years. There's a hint of improvement in the past six months, during which the annualized pace was 2.6%. If this continues, the Fed will be in liftoff mode within months.

One very encouraging thing is the lack of growth of public sector jobs—no growth at all for the past nine years, in fact, opposite a gain of almost 6 million private sector jobs over the same period (see the first of the above two charts). This has contributed to the decline in federal spending as a % of GDP (now only 20.5% vs. 24.5% six years ago), and it is giving more space for the private sector to grow, which in turn augurs well for future productivity gains. That would be a very good thing, since, as the second chart above shows, productivity has been miserably weak for several years running. What the economy really needs is a confidence boost, and increased business investment. Cutting the corporate tax rate seems like a no-brainer that only Washington can fail to appreciate.

Even though this is the weakest recovery on record, it's now set a new record for job security: the lowest ratio of weekly unemployment claims to the workforce. A typical worker is less likely to lose his or her job today than at any time in the past 50 years. Downside risks have declined measurably, but we're left wondering how long it will take policymakers to discover the key to unlocking the economy's tremendous upside potential.

Tuesday, May 5, 2015

Notable and Quotable

Thomas Sowell at his best, distilling fundamental truths that shock politically correct sensibilities:

You cannot take any people, of any color, and exempt them from the requirements of civilization — including work, behavioral standards, personal responsibility, and all the other basic things that the clever intelligentsia disdain — without ruinous consequences to them and to society at large. Non-judgmental subsidies of counterproductive lifestyles are treating people as if they were livestock, to be fed and tended by others in a welfare state — and yet expecting them to develop as human beings have developed when facing the challenges of life themselves.

We're in the early stages of a new bond bear market

I'm crazy to do this, but it sure looks like the Great Bond Bull Market has ended and we are in the early stages of another bond bear market.

The Great Bond Bull Market started in the fourth quarter of 1981, after the 10-yr Treasury yield hit an all-time of almost 16%, and about a year after the year-over-year change in the CPI hit a post-Depression high of almost 15%. It most likely ended 31 years later, in July 2012, when the 10-yr yield fell to 1.4% at the height of the PIIGS crisis, and three years after the CPI hit a post-Depression low of -2.1%.

As the chart above shows, inflation is arguably the principal driver of yields.

By the way, the first bond bear market of the current century started in 1950 and also lasted 31 years. The bear market that is now beginning to unfold will undoubtedly also be many years in the making, and we can only guess at how much yields will eventually rise. I certainly hope they never get as high as they did in the early 1980s, and I don't expect they will.

What prompted me to make this call? It was the recent 47 bps bounce in 10-year German bund yields, off of an incredible low of 0.05% a few weeks ago. Germany, not Japan, can now lay claim to the lowest 10-yr bond yields in history. As the chart above shows, U.S. and German 10-yr yields have been tracking each other pretty closely for a long time, but they diverged significantly over the past year or so. Last month the difference between the two hit an all-time high of 190 bps; German bunds were in the grip of a buying panic, spurred in no small part by intense fears of a Greek default and also by fears of deflation, that subsequently evaporated (a Grexit needn't be an earth-shattering event, and oil prices are up over 30% in the past three months). Since conditions in Europe are not significantly worse than in the U.S., we'll probably see the gap between U.S. and German yields narrow, with German yields rising more than U.S. yields over time. Welcome also to a new German bond bear market.

So here's the big question: does a new bond bear market also mean an equity bear market? My answer: not necessarily, and most likely no. For the next few years, yields are likely to rise only to the extent that economic optimism and nominal GDP expectations rise. Rising yields will be the result of stronger nominal growth, not the nemesis of stronger growth. Besides, the U.S. economy has plenty of room to grow, as I argued last week.

The time to worry about rising yields is when the Fed is tightening and the yield curve is flattening. The two charts above help explain this. In the first, we see that recessions are preceded by a Fed tightening which lifts the real Fed funds rate above the level of 5-yr real TIPS yields (i.e., an inversion of the real yield curve). We see the same story with nominal yields in the second chart: recessions typically follow a period in which short-term interest rates rise enough to equal or exceed long-term rates. Currently, we are probably years away from either of these events happening. The Fed is still extraordinarily accommodative, since real short-term yields are decidedly negative, and they have all but assured us that they will move slowly to tighten. The chart below sums it up: every recession in the past 50 years has been preceded by real short-term rates of at least 3% and a flat or inverted yield curve. Considering that core inflation is currently running about 1.5%, the threat of unpleasantly tight money is at least several years in future.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)